Post-traumatic growth (PTG) on the horizon – Part 2

By Dr. Joe Isbister

Photo by Hide Obara

In my previous blog, Charting our way through the storm, I took a retrospective look at Damien Barr’s Tweet and poem, where he compares the height of the COVID-19 Pandemic to being in different boats, in the same storm. This is how Damien put it:

“We are not all in the same boat. We are all in the same storm. Some are on super-yachts. Some have just one oar.”

In part 1 of this two-part series Charting our way through the storm, I took the analogy further. I described the experience as a ‘collective trauma’, no matter which boat you journeyed in. Here, I explore what it means to describe the COVID-19 pandemic in these terms, exploring the lesser talked about side of trauma: Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG).

Let’s take a closer look at this idea and how you might go about your own ‘post-traumatic growing’.

What is PTG?

Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG) is a theory that explains that trauma-related incidents can be precursors to personal growth. This phenomenon was officially recognised by psychologists Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun, in the mid 1990s. Tedeschi and Calhoun were the first to use the term ‘post-traumatic growth’ to describe what writers, philosophers and artists have known for centuries: People who endure psychological struggle following adversity can often see positive growth afterwards.

The famous 1888 quote from the German Philosopher Nietzche comes to mind:

“That which doesn’t kill me, makes me stronger’.

Or perhaps this was best expressed in the lyrics which Leonard Cohen is best known for, taken from his song Anthem:

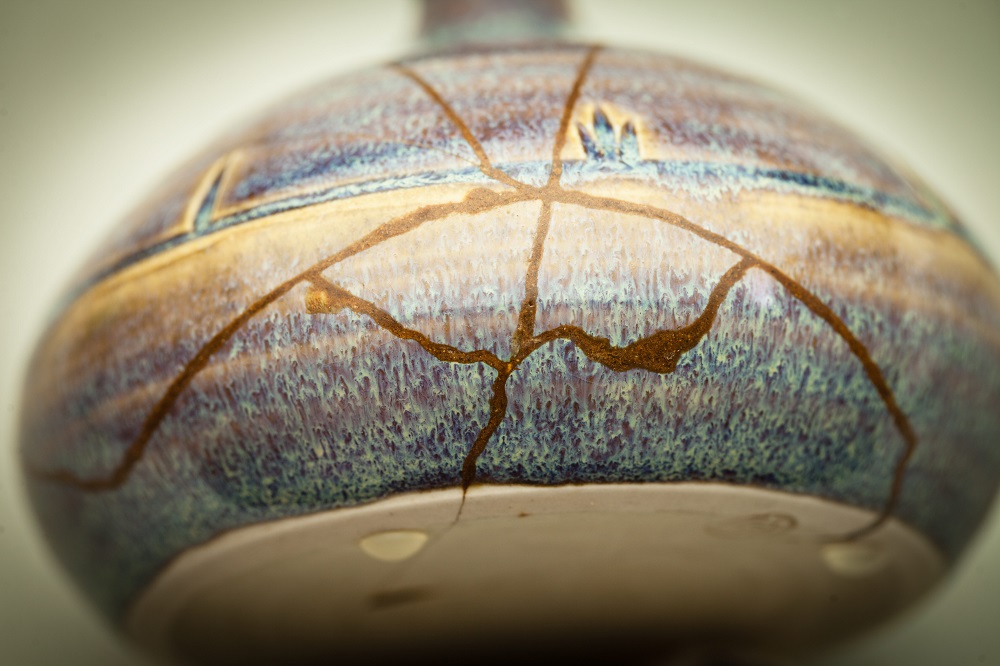

“Ring the bells that can still ring. Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in”.

This concept is also expressed through the classic Japanese art-form of ‘Kintsugi’. The art of fixing cracked pottery not by hiding the cracks, but instead re-joining the pieces with a lacquer of powdered gold, silver or platinum. When the whole piece is put back together, it looks more beautiful, not despite its’ imperfections but actually because of them.

Tedeschi and Calhoun’s research was able to scientifically validate this phenomenon. They then went further by categorising this growth into the following positive themes:

- Greater appreciation of life

- Greater appreciation and strengthening of close relationships

- Increased compassion and altruism

- The identification of new possibilities or a purpose in life

- Greater awareness of personal strength

- Spiritual development

- Creative growth

Karessa Royce’s Story

Perhaps the best way of conveying this is to bear witness to the personal story of Karessa Royce, a survivor of the 2017 Route 91 shooting in Las Vegas. The shooter killed 60 people, wounded 411 people and caused 867 people to be injured.

Karessa rightly believes and proclaims, joy is deeper than happiness. She is the person who stresses about exams and first dates just like any other 22-year-old. She also happens to be the person who was shot and survived the biggest mass shooting in US history.

Karessa is the living embodiment of PTG. A person who, in her own words, makes a choice to ‘keep moving forward’. She refers to October 1st 2017 as her ‘life change event’. She is the person that started to saying ‘yes’ to things. Believed in herself. Practised self-talk. Believed in the possibly of not just “bouncing back but bouncing higher”. For her, growth is all about getting a say in how we live our lives moving forward.

The Paradox of gain and loss

These positive changes are often framed in paradoxes. As Karessa puts it, a type of growth she can ‘both smile and cry about’. The lows help to appreciate the highs. An increased sense of vulnerability, yet an increased sense of your own capacity to survive and prevail. Losses producing valuable gains. Both these losses and gains are experiential, rather than purely cognitive, hence their powerful and transformative effect.

Tedeshi and Calhoun use the metaphor of a seismic earthquake to describe the change. One day we have a particular set of beliefs and assumptions about life. Trauma events shatter that view. We are shaken from our ordinary perceptions and are left to rebuild ourselves and our worlds.

Importantly, Tedeschi and Calhoun’s research also strikes two main notes of caution. Firstly, another paradox; despite these valuable and life-enhancing experiences described by survivors, it would be traded in heartbeat if it could eliminate the trauma happening in the first place. Secondly, expectation of growth following trauma is not an inevitable result.

Growth Conditions

Much like a plant, which only grows well when specific conditions are present, it is similar for post-traumatic growth.

Here are some key post-traumatic conditions that can support the best chance of turning trauma into growth.

- Specific, evidence-based interventions: These may be necessary in order to alleviate the crisis-related psychological symptoms. This will need guidance from trained professionals with expertise in this area. The National Institute of Clinical Excellence Guidelines (2018) include Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Eye Movement De-Sensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR). Matters related to growth occur after a client has had sufficient time to adapt to the aftermath of a trauma. Recovery before growth.

- Listening without trying to solve: Tedeschi and Calhoun advocate relating to a person’s story in a way that sees it through their eyes and helps them value their own experience. To be trite about linking trauma with post-traumatic growth without doing this, would be to explicitly degrade the importance of allowing a person the chance to fully explore their own thoughts and feelings surrounding an event. To the contrary, allowing curiosity about an event, will increase the likelihood that new meaning can be found in the landscape. This might go against learnt behaviours which might naturally lean away from uncomfortable thoughts and feelings.

- Writing: Some of the most well-known research, by Pennebaker in the 1990s, draws upon a great range of subjects (including most notably Holocaust survivors) making a compelling case advocating for the powerful benefits of expressive writing, particularly through diary keeping.

- Embracing Creative Outlets: In her acclaimed book, Artist Tobi Zausner talks about how her own Art was transformed through own personal experience of ovarian cancer. She goes on to describe the experience of both historical and contemporary artists who also went through similarly transformative experiences. As Zausner puts it: “Most of us swim on the surface of life until a storm of illness impels us to dive within and discover new sources of inspiration and strength—yet they were there waiting for us all the time.”

With understanding, time and kindness, there is the possibility of post-traumatic growth. Survivors of this not so easily travelled road, do offer another paradox: Don’t be afraid to look back, but also don’t be afraid to look forward. The horizon might have an ugly storm behind it but the calm after the storm can also include a sunrise.