Your USP – define your unique selling point

In business it’s our USP, our Unique Selling Point, how we distinguish ourselves from everyone else, that makes us different, that makes us special. That’s why people want to buy from us. Our brand is what makes us distinctive. Our USP is the very thing that makes us what we are, our ‘thisness’.

How does your business model deliver a product or service different from, better than, more orientated to your customers than the rest? How do your people, processes and prices align to make your offer so compelling?

Our thisness – Having a distinctive business model

Amazon did it, and continues to do it. Netflix did it, and continues to do it. They are the originals, the ground-breakers, the rule-breakers and innovators, the businesses that have completely changed the way people buy products and services in their sectors. They are great examples of businesses that created astonishing new value by thinking differently about their business models.

There are all sorts of ways of thinking about what a business is, one of the best is to think of each business as having a unique business model that makes their business work. In fact you could say that the business model of a business tells the story of the business and how it works.

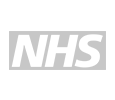

Take Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneurs’ Business Model Generator. It’s a clever way to track the possibilities. Their Business Model Canvas – a single sheet, a single whiteboard – gives you a flexible template for capturing the nine essential parts of a potential business model. A single sheet, a single whiteboard, a single story – this is how my business works! Nine important elements, sure, but one, single, clear story. The nine elements, when combined and aligned, make an effective, distinctive business:

Will you stay or will you go?

This image of the Business Model Canvas and the next come from here. But it could have been created by Jean-Pierre Rivière on Pinterest

The nine elements are:

- Customers – Who are your target customers – are they all the same, or can you segment them into distinctive groups?

- Relationships – what sort of relationship do you want to establish with your customers?

- Channels – How will the enterprise bring its offer or service to customers? What are the channels available to reach them?

- Value Proposition – What do your customers want from you? What do you bring to your customers that they value? Does each customer segment want something specific from you?

- Key activities – What activities are vital for delivering your value proposition to your customers, whether you carry them out or someone else does it for you? When delivering your service or product, what are all the activities you have to make happen to create satisfied customers?

- Key Resources – To deliver your value proposition to your customers, what resources will you need, and how will you replenish them?

- Key Partnerships – What about dependencies? Are there any people or enterprises you might need to link up with to help deliver your value proposition? Who are the vital few beyond the enterprise itself, external people or things you must keep on-side to be successful?

- Costs – What are the costs associated with all your key activities, key resources, key partnerships, and access to the relevant channels? How much does all this activity and enterprise cost?

- Revenues – If the business is to work as a business will your customers pay enough for the product or service to cover the costs you have identified, those you can’t predict and those you’ll need in future? At the end of the day turnover is vanity, profit is sanity, and cash is king. You need a business model that generates profit and cash to survive and thrive.

The Business Model Canvas distils the essence of a company and its processes into a clear framework. It’s clever and practical because it lets you build your business offer and discover that magical pivot point, the MVP – the Most Viable Proposition.

The centrality of values

We like this clarity. It covers most things that need to be covered when setting up a business. The one thing that’s missing from it, in our experience and from our perspective, is the core values, those central to the whole enterprise.

These might be inferred from the value-proposition, which is obviously articulating something that really matters to clients. But values infuse the whole of an enterprise, values determine choices, values inform all decisions, values permeate how a business conducts its key activities.

You could think of the values of a business as a tenth box, a long thin box that runs from the edge of the left-hand side to the edge of the right-hand side. Box ten would include all the things you hold as core, those that inform how you interact with partners, inform how you conduct your key activities, drive the detail behind every customer interaction. You could also think of an enterprise’s values as all the white space that holds the nine boxes together, every commitment we make to the things that hold a business together.

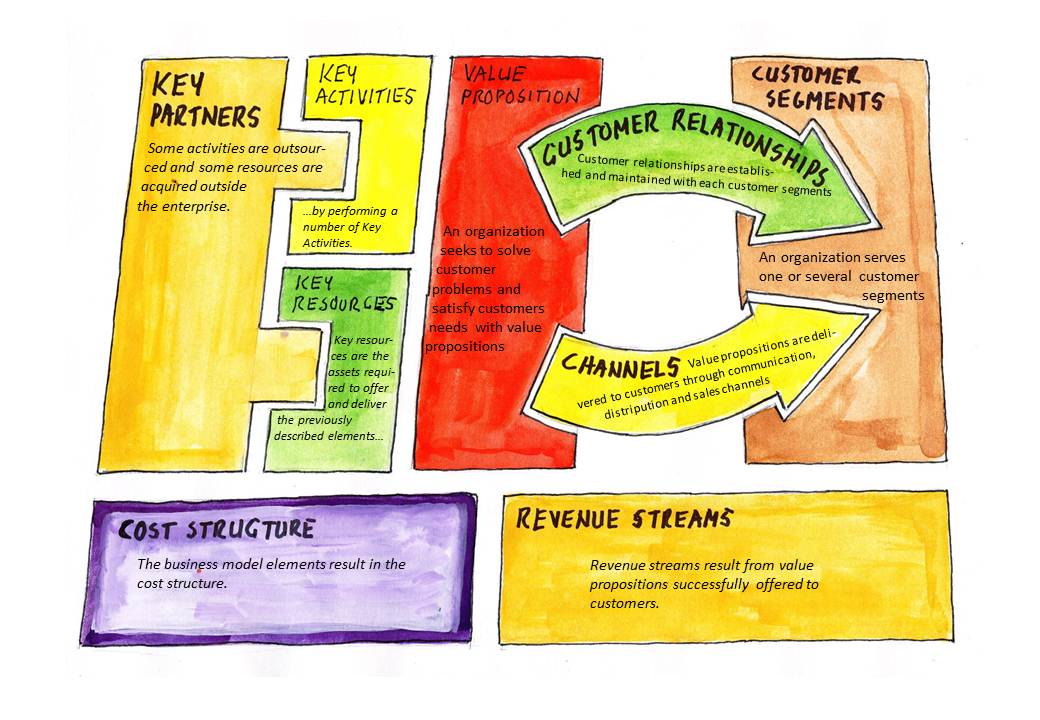

That is what McKinsey was getting at in its original analysis of what made some corporations excellent. In Search of Excellence, Tom Peters and Bob Waterman’s famous business blockbuster of the early 1980s, popularised the important insight that all enterprises are held together by their shared values, as shown in this diagram.

Every business model needs to pay attention to their values.

Our business values help define our distinctiveness, our very particular thisness.

My thisness – tracking my story and articulating it

In jobsearch your personal brand is why people hire you, put your CV on the ‘interesting’ pile, why you stand out from other candidates even though most of them have similar backgrounds and experience to you.

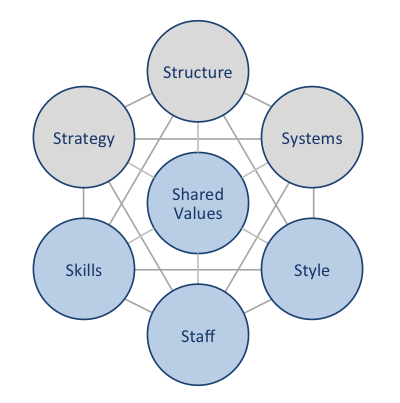

When Tim Clark took Osterwalder and Pigneur’s model and extended their concept to thinking of yourself as a business, they created Business Model YOU. Business Model YOU says you can think of yourself as a business, a collection of nine elements that have to be understood, aligned and presented. In the ‘Business Model You’ the nine categories are re-translated into a person’s core capabilities:

This image is from Agile lean Life

The book is well worth purchasing if you want to find an effective way of presenting yourself.

Getting your DATA straight

Clark, Osterwalder and Pigneur’s Business Model YOU ties in very nicely with how the late William Bridges encouraged people to think about themselves. Bridges was interested in how people thrive in work. As a pundit who read the signs, he noticed how jobs for life were disappearing so he asked himself what do smart people need to do to thrive in this sort of world? In essence he said, each person needs to think of themselves as ‘little mini-businesses’, what he called “You and Co.”. Jobshift, written in 1995, is his prophetic study of the world of work in the Gig Economy, a world without straightford jobs, without jobs for life. It is full of wisdom and insight, but the bit that resonates the strongest describes how we should all know exactly what we have to offer the world. DATA is his shorthand for the concept. As he says:

‘To get yourself out of the bind of always having to look for a job in the same field because that’s what your current experience is, and to maintain your freedom thereafter, you need to get off the merry-go-round of wanting to do something new but only knowing how to do the old thing.

To get off that merry-go-round, you need to ask four questions:

- What do I really want at this point in my life? The answers to that are your Desires.

- What am I really good at? Those are your Abilities.

- What kind of person am I and in what kinds of situations am I most productive and satisfied? That is your Temperament.

- What advantages do I happen to have…or what aspects of my life history or life situation could I turn to my own advantage? These are your Assets.

Together, your Desires, Abilities, Temperament, and Assets represent important and reliable D.A.T.A., a new core that you can build your life around, one that’s more psychologically sustainable because it doesn’t tend to violate who you are and what you really want out of life.’ (William Bridges, Jobshift: How to Prosper in a Workplace without Jobs, 1995.)

If you can answer the above questions fully, and it’s a big if, then Bridges says you’re in the right position to manage your life in this brave new world. To do that you must start managing your career as if it was a business – You & Co, as he puts it.

It’s great stuff. But again, just like Osterwalder and Pigneur’s Business Model, we are surprised by the absence of values in Bridges’ questions. We suggest a fifth question:

What do you stand for?

Making a stand for what matters

As the Canadian Catholic Philosopher Charles Taylor says:

‘There is a certain way of being human that is my way. I am called upon to live my life in this way, and not in imitation of anyone else’s. But this gives a new importance to being true to myself. If I am not, I miss the point of my life, I miss what being human is for me […]. Being true to myself means being true to my own originality, and that is something only I can articulate and discover. In articulating it, I am also defining myself. I am realizing a potentiality that is properly my own.’

‘Knowing my way’, ‘understanding my own originality’, ‘not missing the point of my life’. Knowing and owning and articulating my USP. Charles Taylor is a philosopher, a very interesting philosopher. This passage is an evocation of an ancient idea, the idea of “Haecceity” which translates as “thisness”. It’s a term that comes from medieval scholastic philosophy, a man called Duns Scotus to be precise. He suggested the world was full of many things, but we need to understand the discrete qualities, properties or characteristics of a thing that make it a particular thing. Haecceity is a person’s or object’s thisness, the individual, unique characteristics that make them, them.

For Taylor, our thisness is tied to what we believe is true and good Moderns, people who are engaged in a constant ‘act of becoming’, an ongoing project of self-hood:

‘To know who you are is to be oriented in moral space, a space in which questions arise about what is good or bad, what is worth doing and what not, what has meaning and importance for you and what is trivial and secondary’ Charles Taylor, Sources of the Self: The Making of Modern Identity

Who we are, our identity as people, our thisness as individuals and collective entities – tribes, companies, nations – is an expression of our underlying values. As individuals we need to be clear about the things we stand for. As enterprises we need to make the things that matter to us collectively explicit, and take a stand for them. In Taylor’s words:

‘My identity is defined by the commitments and identifications which provide the frame or horizon within which I can try to determine from case to case what is good, or valuable, or what ought to be done, or what I endorse or oppose. In other words, it is the horizon within which I am capable of taking a stand.’

To thrive in today’s Gig economy we need to think of ourselves as a product that needs a market and must be promoted. The benefits to the consumer, whoever that might be, must be clearly seen, and clearly differentiated.

At this point, of course, your CV and LinkedIn profile take on a whole new meaning – it’s a brochure, no longer a chronicle of your past lives. It has to entice and attract, not ask the reader to take a degree in hermeneutics to get your point. Charles Taylor gives us the rationale, and Osterwalder, Pigneur and Bridges are clearly onto something here, even if it’s only a helpful way to conceive the nature of the career changer’s task.

If what we’re saying here makes sense to you, and you think you would like to become clearer about what is most important to you, please do contact us.