In my last article, I explore the role of luck, concluding that it can be helpful to hold what Derek Muller described as the ‘luck paradox’.

This is the belief that: You are in charge of your own destiny and your successes are down to your own talent and hard work. But also knowing that this is not actually true is helpful. For you or anybody else. This is a strong position because it allows you to simultaneously hold, and benefit from holding two opposing views, each with some truth to them.

In this blog, I take a closer look at what Jim Collins and Morten Hansen, the American researchers, authors, and consultants have contributed towards our understanding of luck. Then in turn, how we can apply this understanding to recent events related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Collins and Hansen would argue that the Luck Paradox embraces the ‘Genius of the AND’. In other words, embracing the flexible and dynamic understanding that things are not either or, they can be both A and B at the same time.

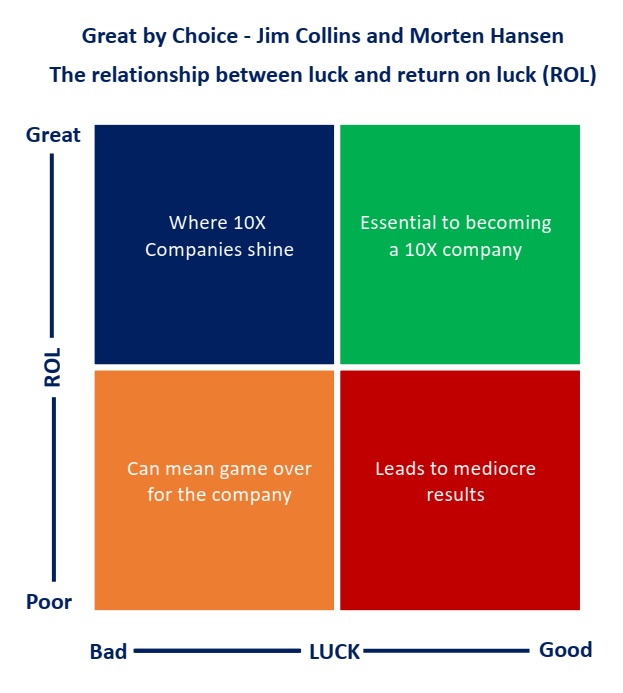

This blog looks at Collins and Hansen’s idea of Return on Luck (ROL). A concept which synthesizes these two extreme positions. If you are interested in learning about this in more detail, I highly recommend classic book Great by Choice (specifically Chapter 7) by Jim Collins and Morten Hansen. This book focuses around the question: Why do some companies thrive in uncertainty, even chaos, and others do not? Utilising a team of more than 20 researchers, Collins and Hansen studied the companies which built their industry indexes by a minimum of 10 times over 15 years. The research team then contrasted these so called 10X companies to a carefully selected set of comparison companies, which failed to achieve these phenomenal returns, under similar conditions.

It’s what you do with luck that really counts

One of the skills when analysing success is recognising what a lucky event is. The first contribution that Collins and Hansen offered was to identify an objective way of categorising whether it was, in fact, luck operating. Collins and Hansen identified that luck is only really ‘luck’ if it stands against the following 3 tests:

- Some significant aspect of the event occurs largely or entirely independently of the key actors in the enterprise.

- The event has a potentially significant consequence, good or bad.

- The event has some element of unpredictability.

Using this criterion, ‘ surprise-surprise’, as a guide, the conclusion was that luck happens. A lot! Both good luck and bad luck. However, the crucial finding was that 10X companies are not luckier than other comparable companies. As Jim Collins and Morten Hansen go on to explain, a bad luck event can lead to a good outcome. Equally, a company can squander good luck and get a bad outcome.

The key difference which determined which quadrant any event landed up in was not luck per se. But rather what they did with the luck they got. In other words, their ‘Return On Luck’ (ROL). In fact, you could categorise each luck event and its outcomes along a four-by-four quadrant. With luck on one axis and ROL on the other.

Morten and Hansen went on to conclude that Luck does not cause 10X success. People do. The critical question is not, are you lucky? It is, do you get a high return on luck?

In Part 1 of my series on Luck, I explored the relationship between the role of luck and the current search for a vaccine to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, it was luck that there were some previous close misses (MERS and SARS), which gave scientists a head-start on understanding Corona viruses. It was lucky that during the Stage 3 Oxford AstraZeneca trials, there was a dosing error which meant a portion of participants received a half-dose, followed by a full dose, which happened to show that it could be gain more efficacy if it was administered that way. At first glance, when analysed according to Jim Collins and Morten Hansen’s criteria, these were luck events.

However, you could also argue that the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine team were primed so that good luck was not squandered. It was down to the visionary thinking of the team, who saw the value in learning about these previous ‘near-misses’, recognising that the knowledge gained through this could be useful in the future. It was something that the Oxford Team did, to maximise this learning opportunity. Similarly, whilst the half dosage was the result of an error, it was only picked up through careful and systematic analysis of the data and close monitoring of the side-effects. Something the Oxford team did, following on from their luck event. In short, the Oxford team did more with their luck when they got it. They recognised a luck event when they saw it. Creating a high ROL.

Similarly, the other successful vaccine teams of Phizer and Moderna were also able to capitalise on a bad luck event, to generate a good outcome. In this case, ushering in the dawn of a new, revolutionary technology: the use of Messenger RNA in medicine. Traditionally, vaccines contain either a weakened form of the virus or purified signature proteins of the virus. A mRNA vaccine is different. Rather than having the viral protein injected, a person receives genetic material, mRNA which provides the instruction to code for crucial parts of the viral protein. Messenger RNA technology is not new. The technology actually dates back to animal studies conducted in the early 1990s. However, progress on using this approach for vaccines had been slow due to mRNA being unstable and easily and easy to degrade, making it difficult to deliver it to the target cell. Previous research on mRNA had been dogged by these difficulties.

Phizer and Moderna recognised the potential value in using the COVID-19, bad luck event, as an opportunity to develop this technology further and overcome these hurdles. Ultimately creating vaccines, in less than 12 months, with efficacy rates that exceeded all expectations.

Here is the great thing

With mRNA, the only thing you need is the sequence of the antigen. Potentially paving the way for this technology to be used as an antidote against future pandemics and treatments for other diseases. For example, there is ongoing research and optimism that mRNA technology could be used to tackle a variety of other health conditions. For example, Multiple Sclerosis.

This is a currently incurable condition that causes loss of motor function and brain degeneration. The disease mistakenly targets cells in the protective myelin sheath that covers nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. There is ongoing research to see if mRNA technology can train the immune system to tolerate (or ignore) myeline. Potentially halting the progression of the disease in its tracks and even restoring lost motor function. There is also ongoing research to see if the same technology could be used to identify and attack tumours, potentially leading to another way to fight cancer. Research is underway to use this technology to tackle herpes, influenza and HIV vaccines. How is that for ROL?

The COVID-19 pandemic may be a one-in-a-hundred-year event. Yet it also uncovered what Collins and Hanse term the ‘Who’ of luck. Namely, brilliant teams of Scientists who could use their knowledge and expertise to turn the tide of the COVID-19 pandemic. Whilst we could never say that the COVID-19 pandemic was an example of a bad-luck, good outcome scenario, this does not mean that good outcomes, even 10x outcomes, can’t also be generated from it.

As Morten and Hansen go onto conclude

We are all swimming in a sea of luck all the time. By definition, we cannot cause, control or predict luck. But ROL is determined by what we do with the luck we receive (both good and bad). Whilst this learning has come from studying 10X companies, there is nothing stopping us applying this 10X thinking and the principles into own personal and professional lives.

About us:

We create the space for leaders to step back, think clearly, and navigate complexity with confidence. By sharpening the narrative that drives decisions, teams, and performance, we help leaders move forward with clarity and impact. Our approach blends deep listening, incisive challenge, and commercial focus—strengthening leadership at every level, from business transformation to boardroom decisions.

“We share resources that help coaches deepen their practice and expand their impact. The articles on this site are designed to spark fresh thinking, offer practical tools, and support the continuous growth of coaches at every stage. “

Jude Elliman

Founder

Our Core Approach:

We work with leaders to sharpen their thinking, strengthen their leadership, and navigate complexity with confidence. Our approach is built around three core areas:

Narrative Coaching – Working with the stories that shape leadership, teams, and organisations.

Commercial Focus – Cutting through complexity to drive clear, strategic decisions.

Challenge & Space – Asking the right questions while creating the space to reflect and grow.

Through this, we help leaders drive transformation, align teams, and make high-stakes decisions with clarity and impact.